Life is a game. The clock is running from the beginning. Often we feel like we are behind. Suddenly we realize it’s the fourth quarter yet we don’t know what’s left on the clock.

The fourth quarter hit when Harrison was very young, before he was diagnosed with autism at almost four years old. It also was about that time that I was placed on work-release from my journalism career. Mary went back to work full-time. I freelanced with editing and writing jobs while taking over the role as primary care-giver and first-responder.

At first this involved getting Harrison to and from preschool in Westcliffe, and a weekly speech therapy session an hour away in Pueblo. One day he escaped from the preschool and after the general alarm was sounded he was located across a side street at the salon where he got his hair cut, knocking on the door and asking for stickers.

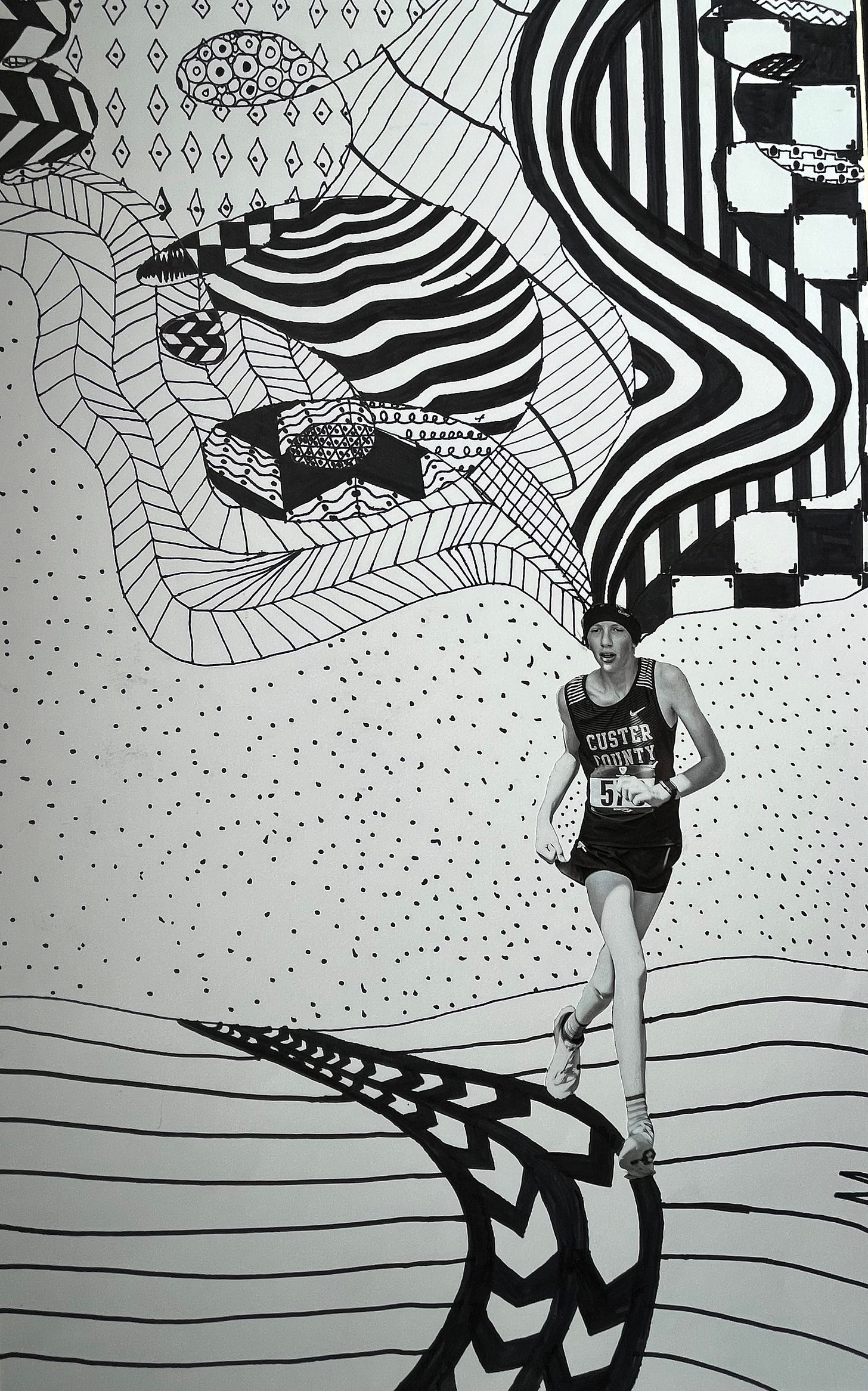

This was not the last time he would run away, and in fact running away would become a recurrent theme and remains so even into adulthood. This is not uncommon among autistic people. Channeling this urge to run into competitive running seemed like a natural outlet, yet it has never kept his mind from running away with him.

When Harrison moved on to the main K-12 school his actions became more serious, and thus began a long stream of answering for his behaviors. Early on his kindergarten teacher picked him up and carried him kicking and screaming to the principal’s office in response to an infraction in class. In second grade his teacher, Leanne, pulled me aside and told me he had been spitting on a classmate. In the years that followed these behaviors would escalate. Soon my cell phone was always within reach and I was on perpetual high alert, ready for an emergency drive to the school.

By the time Harrison was getting ready to advance to middle school, his misconduct had reached new heights. Once I was called to a meeting and sat across from his teacher in a shoulder brace and his aide with substantial bruising from an incident in which they both had tried to restrain him.

Harrison had issues with running away and hiding inside the school. One time I was called in and cornered him as he ran into a faculty rest room and locked himself inside. I decided to wait him out. The librarian gave me a chair and some National Geographic magazines. I sat in the hallway outside the door for the better part of quite some time before he emerged and I peacefully took him home.

One day he demanded cookies from his science teacher’s cabinet and proceeded to get them. At this time Joy, with whom I would later coach track, was his science teacher. Joy told him to return to his seat. He refused. Then, realizing Joy was about to call for reinforcements he grabbed the phone then blocked the classroom door in an attempt to keep his aide from entering. This did not play out well for him and I got the call to bring him home. It was all over cookies.

Another time I was called to the school and found him crying in the principal’s office where he had gone ballistic, needing to be restrained. When I arrived I found the principal, Jack, looking like he’d just gone several rounds in an industrial washing machine. His office looked like a tornado had struck with books and papers flung everywhere. Remarkably nothing appeared to be broken. I offered to help straighten up but Jack waved it off and escorted us to our vehicle with a giant Teddy bear which we buckled in the back seat next to Harrison for the ride home.

Near the end of his elementary grades there was a sequence of events with him striking out at teachers. Each time I was called to the school and he was suspended for the day. This culminated with a call from the principal one day that Harrison was running wild in the school and I needed to get down there.

Several faculty members and I calmly corralled him in a glass-in classroom. I stood outside the door with Joy, who was now the Teacher on Special Assignment (school disciplinarian). By now we had a new principal, Holly, and Joy and I watched through the window as she tried to talk to Harrison and then took a small step closer. He suddenly lunged at her and grabbed her by the throat. I’ll never forget Joy’s gasp. I froze in shock. Before I could even process and respond to what had just happened, the sheriff’s deputies who were standing by were immediately in the room. They had me park my car at the nearest exit and then led Harrison out, one holding each arm, and placed him in the vehicle.

The next day we met with Holly and Harrison was back in school right afterward. He never struck out at a teacher again, though he was still prone to outbursts and tantrums that, while sometimes quite turbulent, were largely controlled by staff.

By now a recognizable pattern had formed. His behaviors were heightened when there was a big change in store, or when his world was spinning out of control and the future was unknown. Which of course it is for everyone all the time, though few of us realize this. For example, the problems at the end of elementary school stemmed from knowing his best friend Mara was moving at the end of the school year, compounded by his approaching move to middle school.

However, he could rise to a challenge when things were properly conceived and lined out for him. When he was in eighth grade it was decided to move him on to the high school resource room a year early. This came with increased expectations. It was a great move. Harrison improved both academically and behaviorally. Although there were some rough spots, I don’t recall needing to bring him home during high school. All of this played into my notion that perhaps college would provide the type of challenges that would result in more personal growth.

Now, nearing the end of his first year at CMC, it seemed he had been shot out of a cannon into an entirely different movie. In middle and high school teachers and administrators were more accepting. In college he might just get thrown out. I felt a lot of pressure to oversee his activities from 120 miles away. His classes and assignments. His social schedule. His workouts, his choices of clothing or footwear. What he ate the day before hard training efforts or competitions. Everything.

Of course I was in control of nothing.

Just like middle school my phone was always at hand. Only now the drive was a lot farther and the stakes a lot higher. He called several times daily and I would walk him through what to wear for practice or how to approach an assignment. I would help him over Facetime find something he lost in his room. I kept a jump bag of necessary items in my truck, always ready to scramble and speed away to Leadville.

Every night I would wait up for Harrison’s call around 10 p.m. We would go over his experiences for the day. We’d discuss what he was doing the next day, and his assignments. Each night we’d go over the same list of bedtime questions. If he had been welding had he showered, or at least washed his face? Did he have his coffee ready to go for the morning? Had he taken his nighttime supplements? Had he brushed his teeth?

These questions were not optional. Forgetting any of these tasks could result in a noisy after-hours outburst in his room, and subsequent care reports.

Still, we could see growth. This shot in the dark at some semblance of independence was paying off. Harrison was doing something improbable — actually something impossible in most minds. He was a college student and athlete just weeks from finishing his first year. He was getting himself to classes, completing assignments, earning decent grades, attending running practices and doing workouts on days he was on his own. And if nothing else, he was on track to earn certificates in basic welding skills.

Notes from The Blur

For my big project in Welding Layout and Fabrication class, my professor Geoff assigned building a welding table for the CMC Ski Area Operations program. The SAO needed a welding table in their building because they commonly made repairs to equipment. Building this table would be the focus of the last six weeks of class.

I was assigned the project along with my classmate Spencer. I thought this would be fun since we would have the opportunity to build something that would be useful and functional, and would remain in use at the college after I was gone. It was also fun to work together with a classmate.

We started by looking at another welding table in the shop. Then, we made a list of the various materials we would need.

The first step was building the legs for the table. These legs would accommodate wheels, so the table could easily be moved to another area in the room without having to carry it. In order to attach the wheels to the legs, we had to weld a tube in each leg. This allowed another piece of metal to be screwed into it. To this we welded a thin square of metal with holes drilled in it to attach the wheels.

After that we worked on the table top and frame. For the frame, we needed four lengths of square tubing. Two of them were the length of the table top, and the two others were cut shorter so they could fit between the longer pieces of tubing. After that, we welded the actual square sheet of metal to the frame.

Also, the open ends of the longer pieces of frame tubing accommodated a leaf that we made to slide into the main frame to hold up longer materials.

After this we welded the legs to the inside of the tabletop frame.

Near the bottom of the legs we welded brackets for a shelf made from expanded steel mesh. This shelf could support a welding machine and also helped to support the legs and frame.

As we neared completion the table would also be outfitted with hooks to hold wires, hoses and tools.

This table project would take up the last weeks of the semester and be finished during finals week.

The Blur Goes to College is a free online book published as a series. Subscribe to receive future chapters delivered by email. If you would like to support our writing, we appreciate upgrades to paid subscriptions.

Soooo good! TY!