Training burros for the long haul

How to prepare your performance donkey for long-distance races

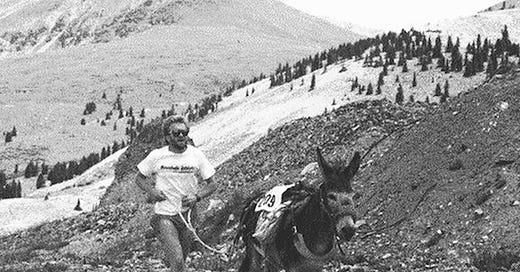

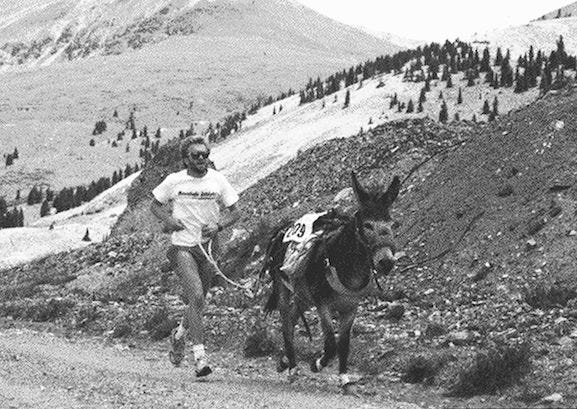

An article on training for pack-burro racing that I wrote about 25 years ago recently surfaced on social media. In addition to other trade secrets, it contained my training log for one week about a month out from the 29-mile World Championship race at Fairplay. That week I ran 76 miles with Clyde but also included some additional running, mountain biking and weight-lifting.

That training volume at least partly explains why we were running the courses so much faster a quarter century ago. In those days winning at Fairplay meant a finish time that starts with a “4.” In fact, I once ran a 4:03 there and finished in fourth place. To place at Leadville you typically needed to run well under three hours.

I am often asked about how to train burros for the long-course races, like Fairplay (29 miles), Leadville (we think it’s about 20 miles), and now the marathon-length (26.2 miles) burro race in California. I’m sure my sensibilities will probably offend some people, so take this all with a grain of stock salt. I know nothing! This is just my perspective from 40-plus years of training burros. Besides, I probably didn’t win seven World Championships on the the 29-mile Fairplay course totally by accident.

Burros need a marathon training program to go long distances just as do their human counterparts. It’s puzzling to me that runners don’t think twice about running an insufficiently trained burro on long courses. The result is much what you would expect — frustrated runners complaining they could run faster if only the burro would, donkeys that end up walking rather than trotting the entire race, and, of course, slower finish times. While it’s not exactly mistreatment — most burros know their rights and act accordingly when pushed beyond their limits by simply shutting down — it is at the very least unfair to expect them to do something for which they are not adequately prepared.

Most training programs for recreational human marathoners recommend a period of 12-20 weeks, building up to 50 miles per week. Some recreational runners can finish a marathon on a base of 35-mile weeks but it won’t be fast. Like legendary pack-burro racer Curtis Imrie said, “If you don’t do it in practice, you probably can’t do it in the race.”

The truth is training a burro to run these distances remains a bit of a mystery after all these years, but a few things remain apparent as my training regimen has evolved. You need to properly balance the training load between yourself and the burro. Some burros like Clyde are a rare exception and seem to thrive on the workouts, while others don’t respond as well to extremely high-mileage. However, good burros with a work ethic will tolerate a moderately high-volume training load, and then do well in long races. Also take into consideration that most burro races do not take place on flat roads at low altitude.

There’s more to it than merely logging miles. Perhaps more important than building the burro’s physical endurance is psychologically adjusting its internal clock. The donkey must be both physically and mentally prepared to go the distance. This means time on the trail. A lot of it.

Back in the day Curtis and I had this saying that “wet saddle blankets” were the key to conditioning burros to run the long courses. We had a good laugh when we learned that people were hosing down their saddle blankets or soaking them in tanks before training runs. What we really meant by wet saddle blankets was that long training runs typically leave them soaked with sweat.

Consider also the difference in the amount of energy expended through the range of a burro’s gaits. We can borrow this knowledge from the endurance horse community, and especially the works of Linda Tellington-Jones, who wrote the book, Strike a Long Trot. Equines proceed from the walk, to a fast walk or walking trot (which can be very useful on steep hills), to a slow trot, fast trot, canter and gallop. Each gait is a step higher from aerobic to anaerobic. Burro racers need to know these gaits, and how and when to use them. For the long races what you mostly want is a ground-eating long trot, as described by Tellington-Jones, keeping the animal right at the upper range of its aerobic capacity. Going just a little faster or to a canter can rapidly get them anaerobic and they will tire quickly unless conditioned for this. This is why you see racers who were first out of town fall off the back a few miles out — the speed is not sustainable. Obviously at a full gallop most people would soon lose control of their burros as these animals are capable of outrunning the fastest humans over a short distance.

I asked one of our local vets, Dr. Kit Ryff, DMV, about training burros from a equine physiology standpoint. He said that while most burros certainly could out-perform humans given an equal amount of training, they still need to be properly conditioned for a marathon-length race. How much? If the burro is in reasonably good fitness, and has been getting regular work, Kit suggested a regimen of five days weekly training for at least two months, and perhaps three, before an endurance event to “leg up” a burro for the distance.

From my perspective that seems about right, though I would add that this should include five to six longer training sessions in the weeks leading up to a marathon distance. My experience is these long runs are best spaced seven to 10 days apart, starting with something in the 12- to 13-mile range and working up to at least 18 miles, with 20 being better. There should be a taper period of about 10 days from the last long run to the race.

Depending on the burro, five days of training weekly may be a good plan. If your burro seems sour or sluggish running this often, then back off to four or even three sessions, so long as one of the runs is a longer effort. Or, forget the traditional seven-day week and go two days on, one day off. At the very least I think the burro needs to be getting 35 miles every seven to eight days, and 40-50 would be better, with a maximum of 65. If you are training a lot more than this, it’s probably overkill and unless your animal has an exceptional work ethic, like Clyde, you are probably running the risk of burnout.

There are some exceptions. Certainly, there have been some seasons when for one reason or another, adjusting to life’s ebbs and flows, my training program has not been what I wished. In these cases my animals fortunately have had months — and even years — of training base to draw upon. For example, if you have been successfully and consistently training a particular burro year-round, including long races each summer, for a couple years or more you may be able to polish out the training with a few weeks of increased mileage, and do quite well. Or perhaps you’ve already been consistently training your burro year-round with a monthly long run.

Another exception is burros who were born in the wild and spent years naturally developing endurance by covering great distances seeking forage, water and safety — so long as they have been kept very active since capture and had some long runs. Once again, it’s individual to each animal and your ongoing training program.

Mixing in hiking and packing can also be very effective endurance training for some burros. For example, starting out with a 30-minute hike for a warm-up, running two to three hours, then finishing with another 30 minutes cool-down hike. A very long day of hiking in the mountains 5-8 hours or more, especially if packing gear, can also help adjust a burro’s internal clock for the duration of a long race.

Kit also noted that for marathon-length races particular attention should be paid to hoof care. If you are training a burro at higher mileage, it’s very likely the hooves will wear down. Consider that the condition of the hoof not only affects the soundness of the burro (No foot — no burro!) but also, more importantly for racing, the actual length of the trot. Short feet equal a short choppy trot. Depending on the burro and the predominant training surface (soft dirt or sand does not wear down hooves the same way more abrasive environments such as rock and hard-packed roads do), you may need to consider shoes or boots. I once ran a set of steel shoes off Clyde in just one week. If he had not been wearing shoes he would have been lame for sure.

So, what if you don’t have the time or inclination to train your burro like this? Perhaps you need to reassess your goals. A longer-term approach may be more appropriate than rushing into a long race with unrealistic expectations, unless you are OK with walking a fair amount of the course. Or perhaps the shorter races are better aligned with your lifestyle and time considerations. Many burros are capable of running competitive races up to 13 miles on fairly minimal training and long runs of 7 to 10 miles, but when you start competing over 20 miles it becomes an entirely different ball game.

I hope this helps people who are trying to get their minds around training for this sport, particularly the long courses. If nothing else, maybe it will inspire some to get their animals out more often and “ramble about the country.” Speaking as someone who has won a few races, and who is practically an anachronism at the finish line of his racing career, when I look back it was not the racing, or even the winning, that brought the real joy and sense of accomplishment — it was the time spent on the trail training these animals.