The evolution of disability rights

31 – From Nazi death camps to college inclusion

Margaret Mead was a cultural anthropologist, and her close friend Erik Erikson was a child psychoanalyst whose theories and books became popular in the 1960s. Erik’s wife Joan collaborated with him in developing his famous Eight Stages of Psychosocial Development. All three professionals were well-known and respected in their fields.

Mead was famous for her theory of developmental imprinting, as well as her research supporting the argument against eugenics, a notion popular with Nazis that some people are simply born genetically superior to others. Her studies supported the notion that humans were largely the product of their upbringing, as well as social and cultural conditioning.

Meanwhile, Erik invented the term “identity crisis” and won a Pulitzer Prize for his book Gandhi’s Truth. Both Margaret and Erik would be considered among the most progressive thinkers of the 20th Century.

Through her work Joan promoted the healing properties of art therapy and also believed in the importance of play, and maintaining playfulness and a sense of humor throughout all stages of life.

Joan and Erik’s fourth son, Neil, was born with Down syndrome in 1944. Down syndrome was known as “Mongolism” at the time. Doctors urged Erik to send Neil away to an institution immediately. People with disabilities such as this were stigmatized and excluded from society during this period of history. The attitude was that children born this way were a huge burden to their parents and society, and that raising such a child was a traumatic and overwhelming undertaking.

While Joan was still under sedation, Erik asked Margaret her advice on what to do about Neil. Margaret agreed with the doctors. Erik made the decision to send Neil away and signed the papers before Joan regained consciousness. Erik told their other three children that Neil had died in childbirth. Neil lived out a sad existence in an institution and died at the age of 22.

Oddly, Mead’s later career seemingly reflected a different attitude, She became an advocate of disabilities rights, speaking out against eugenics and, ironically, institutionalization, and serving on the President’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped under President Lyndon Johnson.

Erikson’s decision, supported by Mead, to send his son away to an institution, happened during World War II when an even more gruesome attitude was taken to an extreme by the Nazis in Germany. Under Action T4, a secret Nazi program, physically and mentally/intellectually disabled people considered “life unworthy of life” and “worthless eaters” were put to death.

Beginning in 1939, the Nazis rounded up disabled children, including many with autism, from families and sent them to institutions. The families would later receive a letter saying their child had died of natural causes. Actually the Nazis were sending them to gas chambers, literally perfecting the extermination techniques they would later use in the Jewish Holocaust, which began two years later. It’s estimated that more than 70,000 physically and intellectually disabled people were put to death in the Nazi’s T4 program.

The evolution of civil rights is a curious process. It’s compartmentalized and exists in a time warp. Society should treat everybody fairly and equitably, always. But that’s not how it works.

It took a century to get from the U.S. Civil War to the U.S. Civil Rights Act, passed in 1964 along with Title VI, prohibiting discrimination in educational institutions against people by race, color or national origin. Astoundingly, it was not until 1972 that the Equal Rights Amendment passed (but was never ratified) giving way to equal educational rights for women. (I was attending a “racially integrated” junior high school in Las Vegas, Nevada, when this happened.)

Almost two decades later, in 1990, The Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act and Americans with Disabilities Act became law. Between the two, these acts advanced rights in public schools, the workplace, and in both public and private universities and colleges — including academic programs as well as student housing and dormitories.

Federal law provides necessary modifications to academic requirements for courses of study if requirements negatively impact a student with a disability. Modifications are determined on a case-by-case basis in consult with educators and by reviewing the course description. Educators do not have to waive or change requirements deemed essential to the course, or if the changes would fundamentally alter the program.

Some common academic accommodations include extra time for exams, taking exams in quiet locations, or alternative means of assessment. In some cases educators may substitute courses required for completion of degree requirements or modify the courses themselves.

Despite these measures being in place, the number of autistic students attempting college is very low, and the percentage who drop out of college is very high. Even well-meaning administrators may not be aware of the many challenges associated with including neurodivergent students — or the rules, laws and programs in place to support them. Also there are plenty of loopholes and gray areas that may leave the door open for marginalization.

Today educational rights are a no-brainer for students of any gender, race, color, and those with physical disabilities. For those with intellectual disabilities it’s not always so clear-cut. Disabilities rights clearly are civil rights, but their limits warrant further exploration.

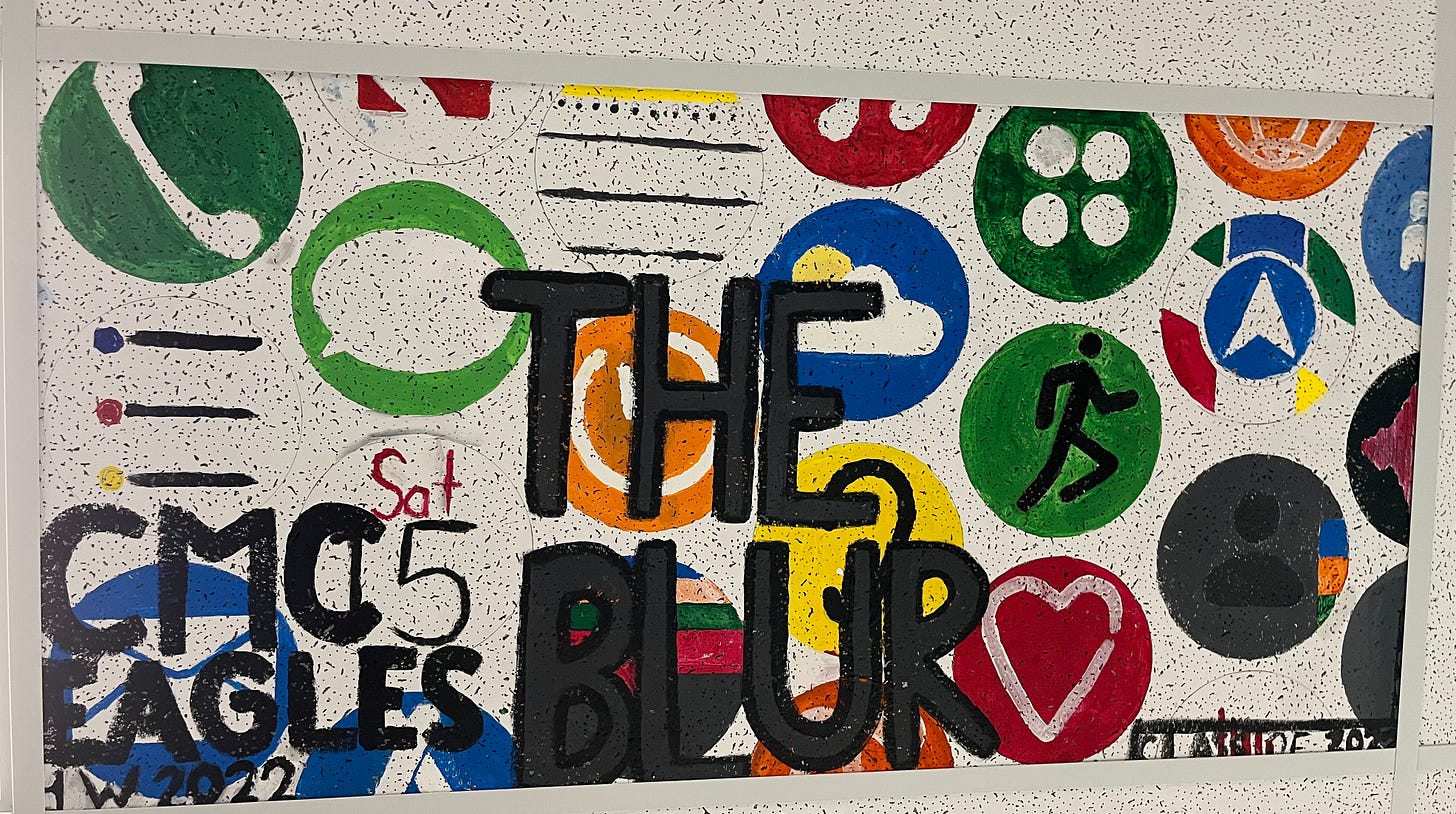

The Blur Goes to College is a free online serial book. Subscribe to receive future chapters delivered by email. If you would like to support our writing, please upgrade to a paid subscription, or donations are gratefully accepted via Venmo @Hal-Walter (phone# 8756).